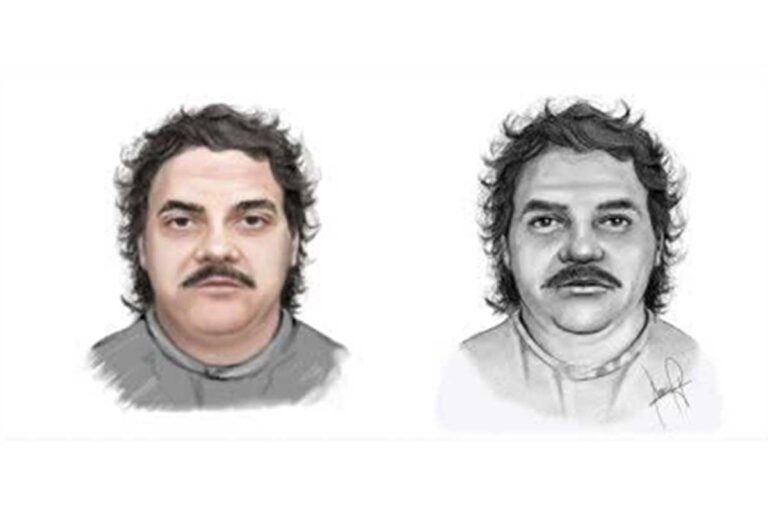

TORONTO—He was found where the city loosens its grip—near the Don River and Queen Street East—on July 26, 2002. No wallet. No papers. No one pacing the shoreline asking questions. Toronto Police say foul play was not suspected. Just a man, unnamed, carried out of the water and filed into a system that is very good at holding onto bodies and very bad at holding onto stories.

Twenty-three years later, that man still has no name.

But the story has begun to speak.

Through Investigative Genetic Genealogy, Toronto Police have learned that most of his ancestry is Indigenous, rooted in Manitoulin Island and the Algoma region, braided with French and Acadian lines. Two-thirds Indigenous. One-third European. A familiar map to many families here. His DNA shares common ancestors with people carrying surnames long etched into Island life: Pine, Corbiere, Toulouse, Migwans, Debassige, Roy, Vincent, Jimagan, Waboose, Picody, and Sissenah. Police caution that his surname in life may have been something else entirely.

This is not a family tree you pass without stopping. It is a thicket of relations, doubled and tripled through generations of intermarriage, kinship and survival. According to Toronto Police Service Detective Constable James Atkinson, updated DNA testing has produced many matches—none close enough yet to restore his name. X-chromosome matches point strongly to Manitoulin Island on his mother’s side. On his father’s side, the genetic trail leads toward Mississauga First Nation near Blind River.

The earliest confirmed maternal ancestors are Marie Roy, born May 24, 1817, and Henri Corbiere, born around April 2, 1823—both believed to have been born on Manitoulin, possibly in Wiikwemkoong, and later passing in West Bay/M’Chigeeng First Nation in 1917 and 1918. Paternally, most matches trace back to descendants of Joseph Vincent and his wife Angelique, who settled around Mississauga First Nation in the mid-1800s.

Police have spoken with many families. Several possibilities have been ruled out through close familial DNA testing. As of December 12, 2025, Detective Atkinson says no one has yet come forward to identify this man or his family.

A renewed call for help has been circulating online with locals sharing the details publicly in hopes they might reach someone in Algoma or on Manitoulin who recognizes the outline of a life gone missing.

Statistics paint a stark backdrop to this case. Indigenous men and boys in Canada face homicide rates up to seven times higher than non-Indigenous men. They are also killed at rates three times higher than Indigenous women. In 2020, 81 percent of Indigenous homicide victims were men—the highest proportion recorded since 2014. Investigations have identified more than 600 missing and murdered Indigenous men and boys since 1974, with researchers cautioning that the real number is likely much higher.

Yet their names rarely anchor national conversations.

Much of the public reckoning around violence against Indigenous people has rightly focused on women, girls, and Two-Spirit people. The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit People inquiry forced a country to look at what it had long ignored. But even within that necessary reckoning, Indigenous men and boys have remained largely peripheral—acknowledged, yes, but often still unseen.

They should not be.

Indigenous men are victims in the majority of Indigenous homicides in recent years. Many are young—the average age hovering around 31. Many come from regions like the Prairies, but the pattern stretches coast to coast. Studies and investigations have repeatedly pointed to underreporting, police indifference, and systemic racism as barriers to justice. Families are told their loved ones “ran away.” Files go cold. The urgency drains out of the room.

This man—found in Toronto, with Island bloodlines and no one yet to speak his name—sits squarely inside that silence.

Police note that he was likely born around the era of the Sixties Scoop, a time when Indigenous children were routinely removed from their families and communities, scattered across provinces, renamed, and raised far from their relations. If that is the case, it may explain why the genetic map points north while his body was found hundreds of kilometres south. It may explain why no one recognized him right away. Disconnection was policy then. Its echoes are still loud.

Toronto Police have placed his DNA profile on two public genealogy platforms, FTDNA and GEDmatch, and are now working painstakingly through distant matches, hoping someone will opt in, compare, remember. Detective Atkinson stresses that in every one of the roughly 25 cases his unit has solved using genetic genealogy, families had to step forward. Science can open doors, but it cannot walk through them alone.

This is where the Island comes in.

Somewhere in a family album, there may be a man whose story trails off in the late 1990s or early 2000s. Someone who stopped calling. Someone whose absence was explained away by distance, addiction, shame or the assumption that he simply didn’t want to be found. Those assumptions are part of the larger story, too—a story in which Indigenous men are expected to endure, disappear, or be blamed for their own erasure.

If you have knowledge of a missing family member, or believe you may have information that could help identify this man, you are asked to contact:

Toronto Police Service

Homicide & Missing Persons Unit

(416) 808-7411

Detective Constable James Atkinson

james.atkinson@tps.ca

Further information is available through the RCMP Missing Persons database under case number 2006003699.