MANITOWANING—Sixteen years ago, the Six-Foot Festival emerged from humble beginnings, and has since grown into a vibrant celebration of imagination, collaboration and cultural expression that extends far beyond the borders of Manitoulin Island. What started as a local experiment has evolved into a cherished community tradition that now brings together artists, musicians, storytellers and curious community members to share in the process of creation, in the spirit of expression and interpretation.

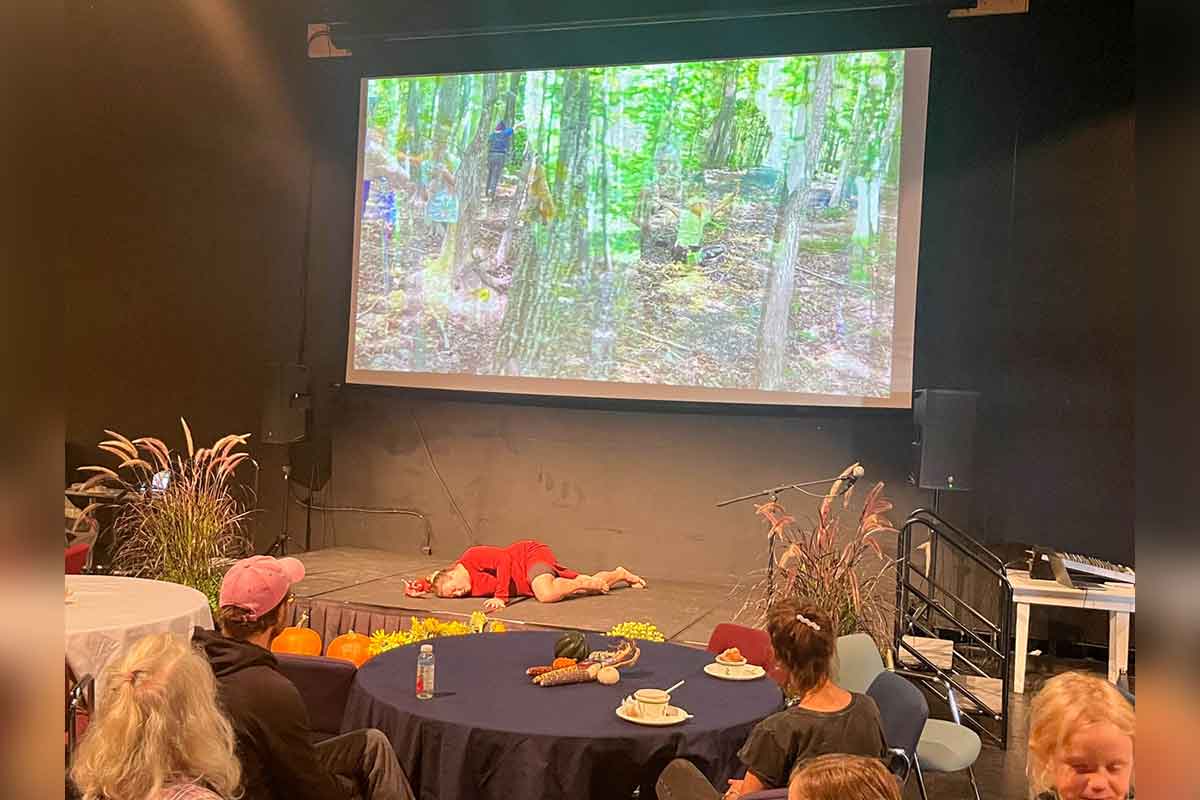

This year, the festival took place on Friday, September 26 and Saturday, September 27, at the charming and welcoming Debajehmujig Creation Centre in Manitowaning. The 2025 theme, Aki Noo’ooma—“The Earth’s Language”—asked its artists to explore and interpret how the land itself communicates and how humans might come to better listen. The result was a rich collection of exhibits, performances, storytelling, food, and interactive installations, each offering a different way of hearing and responding to the earth’s subtle messages and teachings.

Festival founder and operator Ashley Manitowabi reflected on the event’s continued growth. “I think it was pretty successful seeing new people coming in on both Friday and Saturday,” he said, noting that 15 artists participated in total. However, it was originally slated for 16, a fitting, but coincidental number given the anniversary of the event. Sadly, one artist had to step back following a family loss.

This year, Mr. Manitowabi himself returned to cube-building, a central tradition and method of the festival. “I did a cube this year, though I haven’t in several years. I did it as part of Ontario Culture Days, as one of eight participants, and I began thinking about how I can give a voice to the four teachers—the birds, the animals, the plants and the fish. I carved each of these in my piece, and all four were represented in all of this.”

He explained that the creative process was deeply personal, shaped by the challenges of living close to the land on his homestead. “Emotions were heightened because of a bear that was local and was eating my crops of vegetables and cherries. I found myself being frustrated, but I challenged myself to change my perspective from being frustrated to seeing it for what it was and as a learning experience in what I could learn from the experience.”

Mr. Manitowabi’s cube stood tall among the others, built from tree rings salvaged from trees felled by time, weather or animals. His work was paired with an educational component. “This year, I also did two workshops, where people got to create their own miniature versions of my work out of branch discs for which of the four teachers they would want to learn from over the course of the years,” he said. “So there were several smaller versions and plaques at the back of the main hall, which had several of these images in them. A few people took part on the Friday, but on Saturday, there were several other people taking part, and by the end, there were at least a dozen pieces to display.”

Like the festival itself, the workshops encouraged people not only to observe art but also to take part in the creative act, thereby bridging the gap between artist and audience. Through these interactions, it invited guests to not only be complacent observers but also artists in their own right.

Looking ahead, Mr. Manitowabi stressed that community feedback is important to planning the ongoing direction of the event. “In terms of planning next year’s event, we usually start planning for future events right after the first one is done. We listen to feedback and try to come up with things that people have said they might want to see or ideas that we might not have considered.”

The process is an organic thing, fitting given the natural themes which define the festival. “We’ll be trying to figure out where we are headed in the following weeks, and then we’ll start trying to attract new artists to participate. We are always looking to make people feel welcome, and that’s very important to us. We always say we want our space to become your space.” Mr. Manitowabi said that this is because the creation process can be intimate for many people. “They need to feel comfortable and they need to feel welcome into the areas where they will be creating or displaying their works.”

This emphasis on welcome extended beyond the visual arts on display in the centre. “This was also a big first for us as we had our first annual open mic,” Mr. Manitowabi shared proudly. “People were playing acoustic original music, as well as a woman from out of town who came and did her own poetry. We have begun to find that people are coming from all around. This year, the longest was our mural artist outside, who came from northern Manitoba.”

That artist was Waabivii Courchene, who worked throughout the weekend on a mural titled Sagkeeng. Her work depicted the Thunderbird and the serpent—two forces of nature often seen as oppositional, though in her interpretation, they coexisted as necessary counterparts. “It’s a piece which features the Thunderbird and serpent. It’s a visual form of storytelling. The two are natural opposites, though neither is seen as good or bad. Rather, they are both needed to keep balance,” Ms. Courchene explained.

She described her inspiration as rooted in Anishinaabe oral tradition: “The piece is a loose reference between the two, and it talks to a concept known as hollow water, where the serpent had the Thunderbird trapped under water, because the serpent is a water creature, and this led to the creation of islands. It’s all part of an oral legend.” Ms. Courchene noted that the work would be completed in the coming days and encouraged those interested to follow her work on Instagram at @waabiivii

As the festival drew to a close, the sense of togetherness it created remained. The Six-Foot Festival is never simply about what appears on the stage, the cubes, or the walls of the hall. Instead, it is about what happens between people, between artists and their audiences, and between the community and the land that sustains them. The theme of Aki Noo’ooma—“The Earth’s Language”—was more than a guiding phrase. What it manifested most clearly was that art provides an entry point into deeper, more meaningful dialogue. Mr. Manitowabi’s story of frustration and renewal when a bear threatened his crops resonated with many attendees.

Similarly, Ms. Courchene’s mural placed legend and ecology side by side. The Thunderbird and serpent were not cast as adversaries but as necessary forces that generate balance. Her imagery echoed the lesson that not all conflicts need to end in defeat; some exist so that equilibrium can be restored.

Other artists contributed a verse to the discourses. Bruno Recollet’s “Skull Rocks” asked visitors to look twice at what might otherwise have been dismissed as ordinary stones, while Chantal Filion’s soil-filled boxes whispered of time’s endless cycle of decay and renewal. David Plant’s medicine wheel installation invited participants into his personal process of reconciliation, and Lynda Trudeau’s cedar branch installation offered shelter, stillness and a chance to reflect on what it means to care for one another, among many other contributions from artists and patrons. Each piece reinforced the idea that communication extends far beyond words—it is often found in the texture of wood, the scent of cedar, the taste of food, and the rhythm of movement.

In celebrating its 16th year with a proposed 16 artists, the Six-Foot Festival demonstrated that creativity is a communal act. It is not limited to those who call themselves artists; it belongs to anyone willing to step forward, take a risk, try, and share. The festival continues to be a space where people can come together not only to witness but to take part in that process.