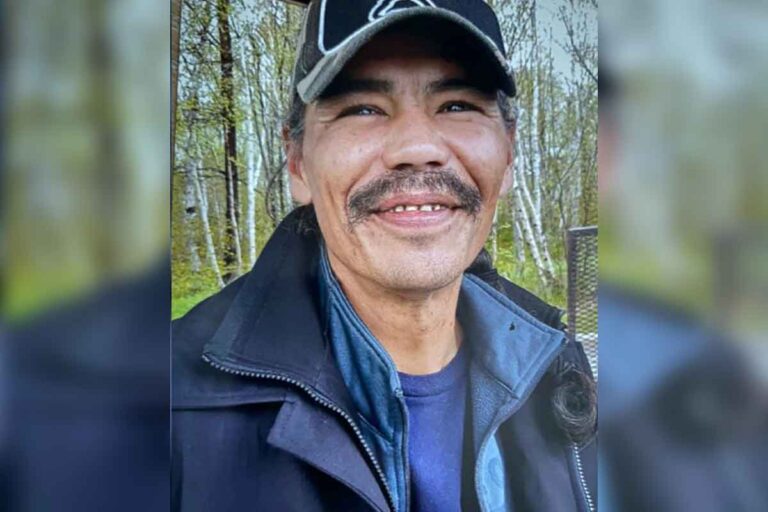

SUDBURY—Four years after the death of 44-year-old Justin Alexander Trudeau at the Sudbury Jail, a coroner’s inquest has laid bare what many have always known: that Ontario’s jails are ill-equipped to keep people alive. The five-member jury issued 13 recommendations last week, urging the province to ensure that medical care in correctional facilities meets even the most basic standard of human dignity—including having a nurse on site 24 hours a day.

Mr. Trudeau, from Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory, died on February 13, 2021, just five days into a 30-day sentence. The post-mortem revealed a severe antibiotic-resistant infection that spread from his lungs into his bloodstream. He had reported difficulty breathing and rib pain. The night before his death, he called his mother, Brenda, gasping for air and asking her to bring an inhaler.

By the time guards found him the next morning, he was already gone.

The inquest heard testimony about shortages of both nurses and correctional officers, miscommunication between shifts, and the absence of overnight medical staff. Dr. Dominic Mertz, an infectious disease specialist, told the jury that closer monitoring could have caught signs of sepsis, a fatal condition if left untreated.

Key measures include hiring additional staff and ensuring 24-hour nursing coverage, as well as having a dedicated staff member to manage medications so nurses can focus on inmate care. The jury also called for clear standards for inmate monitoring, especially during overnight shifts, and for segregation cell windows to be retrofitted to allow better visibility.

Improved communication between correctional officers, particularly during shift changes, and training on clear, detailed documentation were also emphasized.

Health care recommendations include enhanced monitoring for infections, especially sepsis, and mandatory training for nursing staff on recognizing and responding to septic shock. The ministry was urged to move forward with the implementation of electronic medical records (EMR) to improve continuity of care.

Finally, the jury called for expanded education for staff on the needs of vulnerable populations, including those facing homelessness or substance use challenges, and for reconciliation-focused cultural safety training that integrates Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into correctional practice.

It is a grim irony that Mr. Trudeau died isolated in a cell meant for COVID-19 observation. February 2021 was the height of pandemic restrictions, when vaccines were just beginning to reach long-term care homes, but far from the reach of provincial jails.

At that time, Ontario’s vaccination rollout for inmates had not yet begun—it would be another month before the first doses arrived in some facilities, and several more before others were reached. By June 2021, more than 6,700 prisoners across Canada had tested positive for COVID-19, an infection rate many times higher than in the general population. Yet less than half of Ontario’s incarcerated people had received a first dose.

The lockdowns meant to protect inmates from infection also worsened conditions inside. People were confined to their cells for long stretches, with little access to medical care or the outside world. Indigenous cultural supports—already limited—were halted almost entirely. Elders and cultural workers were cut off due to public health measures, replaced by patchy phone lines and virtual calls that few could access privately. The pandemic, in other words, didn’t create neglect; it amplified what was already systemic.

Across Canada, Indigenous people remain disproportionately incarcerated, a legacy of policies that criminalize poverty, addiction, and trauma. In Ontario, the Indigenous incarceration rate sits roughly six times higher than for non-Indigenous people. The factors are painfully familiar: intergenerational trauma, inadequate access to health care, systemic racism, and the over-policing of Indigenous communities.

At the inquest, coroner co-counsel Robert Kozak thanked Mr. Trudeau’s family for their courage and patience in reliving their son’s final days. “The purpose of this process,” he said, “is to prevent future deaths.”

Whether these recommendations will do that remains to be seen. They are not legally binding, and history has shown how easily such promises fall away once the spotlight fades.

But if Mr. Trudeau’s death forces the system to confront its failings—if it compels this province to place a nurse where there was once only silence—then perhaps something more than loss can come from it.

As his mother said during the proceedings, “He was asking for help.”

This time, the system might listen.